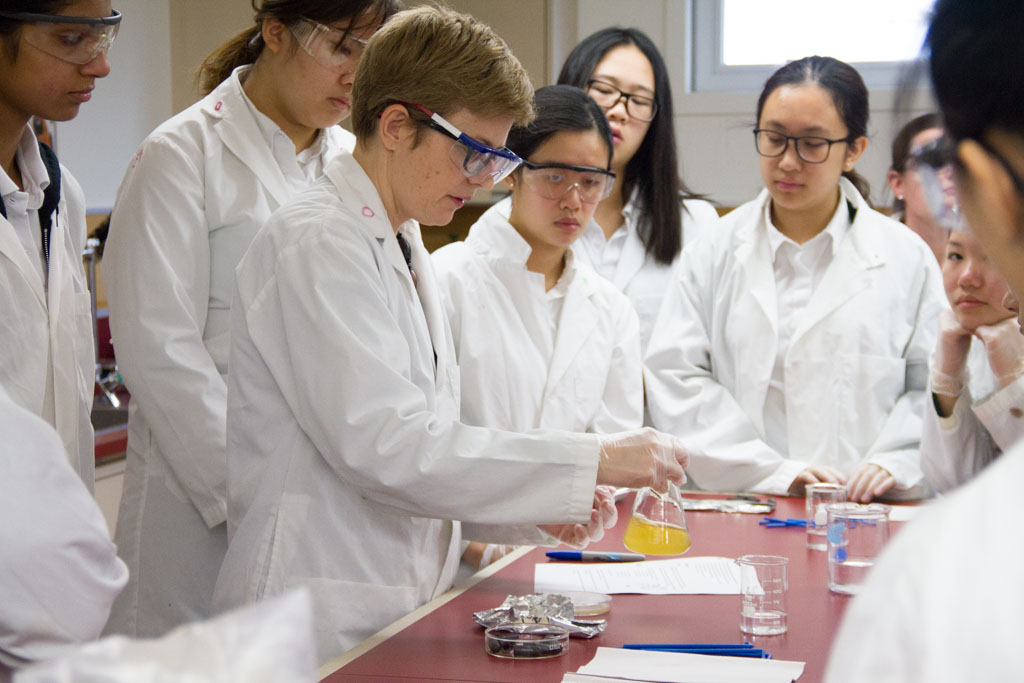

A few weeks ago, the Biology 11 classes were transported into the middle of a real-world crisis scenario. Instead of entering their regular classroom, they entered a “quarantine” room decorated with white plastic sheets and “biohazard” signs. They were asked to protect themselves with masks, safety glasses, lab coats, and gloves.

“Woah… this is just like something from ‘The Magic School Bus’!” one girl exclaimed. “You are now part of the World Health Organization and there is an outbreak of disease,” I told them. “It’s up to all of you, as medical epidemiologists, to create a plan to stop the disease from spreading. Thank you for your commitment to global health!”

In order to learn more about the impacts of viruses and bacteria on human health, the Biology 11 classes are approaching the subject using problem-based learning. Originally designed at McMaster University in 1961 to help medical students become better doctors, problem-based learning teaches content in conjunction with the collaboration, critical thinking and decision-making skills essential in real jobs. Outside of school, none of us have careers in which someone tells us to memorize a set of facts, then present them to clients. Real life is about problem solving and collaboration. Fortunately, the new BC curriculum has also shifted its emphasis towards developing the kinds of skills that help students succeed while becoming 21st Century learners. In addition to the biology of microorganisms and the human immune response, the girls are learning issues relevant to global health and how to work together to create solutions.

Upon receiving the first round of patient information, the girls quickly got into the spirit of the scenario and set to work analyzing symptoms to identify the disease. The Biology 11 classes also conducted their own experiment using household products to see which one is most effective at limiting bacterial growth without the danger of bacterial resistance from misuse of antibiotics. The results of their research may be used in their outbreak control plans in the event that the disease is bacterial or to prevent the spread of secondary infections.

The outbreak scenario was set in Kinshasa, a vibrant, bustling city in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In order to fully understand how diseases can be contained, the Biology 11 students have had to expand their knowledge of the culture and geography of the DRC, learning about what local citizens and health units would need to treat the sick and prevent further spread. They have been working hard to analyze their own biases and find ethical treatments.

Consultation with experts is also a skill many of us use in the workplace, and the class has been extremely fortunate to have several guest speakers lend their expertise to the solution. Noble Kelly, one of our own York House teachers, is the founder of Education Beyond Borders, a non-government organization that helps train educators in developing African countries to have the tools for positive community outreach. His discussion with the Biology class on culturally sensitive ways to help the local people in DRC and some of the infrastructure and economic difficulties they might face was incredibly eye-opening.

The girls’ learning experience is also connecting with the real careers in Biology. Two Epidemiologists from UBC have also volunteered their time and expertise to help the class with its outbreak control plan. Ms. Kaitlyn Harper, a Masters student in Epidemiology, spoke to the classes about a local outbreak example (the E. coli outbreak and flour recall in 2017). She was available to collaborate with students on how to communicate their outbreak plans. During the final presentations of the outbreak plans on February 14th, Dr. Rosemin Kassam, a celebrated Epidemiology professor at UBC, visited York House to offer her feedback on their final products and help celebrate what the girls have learned about Epidemiology.

While the Biology 11 class routine over the past few weeks has looked and felt quite different than normal, and I have been impressed to see how the Biology 11 “epidemiologists” are approaching a real-world problem. They are asking questions, making decisions about their own learning, and navigating collaboration difficulties to find solutions. There’s no question that it’s a challenging multi-level problem, and there is no one “right” answer as a solution. What the Biology students are learning is a little slice of how to apply their knowledge in the real world, and the process of how to do that is a lesson that will hopefully stick with them for life.

Lisa Marcos

Biology Teacher